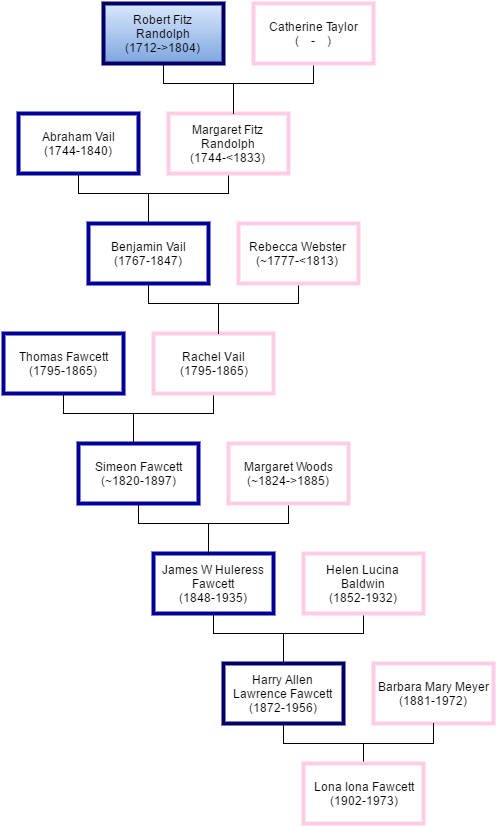

Robert Fitz Randolph (1712-~1803)

Birth

Robert Fitz Randolph was born on 19 Jul 1712 in Woodbridge, Middlesex, New Jersey as the fifth child of Edward Fitz Randolph and Katherine Hartshorne. The date was listed as the 19th day of the 5th month of 1712, but double dating was still in use, so the first month was March and the fifth month of the year was July. Robert had nine siblings, namely: Richard, Edward, Thomas, Mary, Nathaniel, Margaret, Eseck, Hugh, and Hartshorne. His parents were members of the Society of Friends, commonly called the Quakers. Robert’s birth was recorded in the Quaker records.

Marriage and Children

By the time he was 26, Robert Fitz Randolph had married Catherine Taylor, daughter of John Taylor and Sarah Hartshorne. The exact date of their marriage is not known, but they were wed before 20 Feb 1739 in Essex, New Jersey. Catherine and Robert were cousins who married “out of the unity of Friends.” Catherine’s mom, Sarah, was a sister to Robert’s mom, Katherine, so they were first cousins. They married out of meeting, which means that they did not go through the normal procedures within the Society of Friends to get approval for their marriage. Normally, a Quaker couple would declare their intention to marry to the women’s meeting where the would-be bride attended, in other words, to the women’s group of the congregation in which she participated. A committee would be formed to review the request and to make a recommendation on whether or not the marriage should proceed. If the women approved, then it would go to the men’s meeting. If they approved, then the couple could be wed. But, Robert and Catherine, for whatever reason, did not go through the process, but married anyway. They were perhaps given a reprimand of some type, but were allowed back to the church as their children were recorded there later.

Robert Fitz Randolph and Catherine Taylor had the following children:

- Sarah Fitz Randolph was born on 15 Jan 1739 in Essex, New Jersey. She married Mootry Kinsey on 26 Jan 1764 in Woodbridge, Middlesex, New Jersey.

- Robert Fitz Randolph was born on 10 Dec 1741 in Essex, New Jersey. He married Sarah Taylor. This Robert was known as a Fighting Quaker. In 1771, he moved his family to Northampton which is now in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. Then in 1773, they moved on to Northumberland County and then further on to the western frontier of Pennsylvania. In 1776, the Native Americans tried to reclaim their land. Many settlers were killed and most of the rest, including Robert’s family, were driven from their homes. Robert and Sarah took their family to Berks County and returned a year later to their deserted home. Robert joined the militia and fought in the battle of Germantown on 3 October 1777. After their settlement was attacked again, the Fitz Randolph’s returned to their native New Jersey. He served in the Revolution until the close of the war, then in 1783, returned to Pennsylvania. When the war of 1812 broke out, Robert was 71 years old, yet he started out to volunteer alongside four of his sons and two of his grandsons. He was eventually persuaded to return home. He died on 16 Jul 1830 in Meadville, Crawford, Pennsylvania at age 88.

- Margaret Fitz Randolph was born on 01 May 1744 in Essex, New Jersey. She died before 1833 in Menallen, Fayette, Pennsylvania. She married Abraham Vail on 28 Aug 1766 in Essex, New Jersey (Woodbridge Monthly Meeting).

- Edward Fitz Randolph was born on 05 Jul 1746 in Essex, New Jersey. He died in 1748 in Essex, New Jersey.

- Mary Fitz Randolph was born on 02 Apr 1749 in Essex, New Jersey. She died on 23 Aug 1753 in Essex, New Jersey.

- Katharine Fitz Randolph was born on 22 Dec 1751 in Essex, New Jersey.

- Hope Fitz Randolph was born on 07 Aug 1754 in Essex, New Jersey.

- Taylor Fitz Randolph was born on 21 Aug 1756 in Essex, New Jersey.

- Mary Fitz Randolph was born on 02 Jan 1758 in Essex, New Jersey. She married Stephen Vail before 19 Jun 1771.

As is demonstrated by the preceding birth records, it was not uncommon for his name to be recorded as Robert Randolph or Robert F Randolph instead of Robert Fitz Randolph.

Piracy in the family?

It was written that Robert Fitz Randolph was known as Captain Robert because he worked as a sea captain for many years. No evidence of that has been found yet. But, he was a minor part of a big story involving piracy on a ship commanded by his first cousin, Samuel Fitz Randolph.

The story is a little lengthy, has a ton of characters and, unfortunately, we don’t know the ultimate outcome, but it seems that Samuel Fitz Randolph ended up in possession of a lot of Spanish money – pieces of eight – that wasn’t his…

Captain-General Don Juan Manuel de Bonilla of Spain was in command of a Spanish treasure fleet of about eight ships. They were carrying large amounts of sugar, cotton, vanilla, cocoa, plant seedlings, copper, hides, cochineal and indigo for dyes, and as many as three hundred chests of silver containing Spanish money – in total, about 400,000 pieces-of-eight. The armada also carried prisoners and important passengers such as the president of Santo Domingo and the governor of Havana and his family. They left Havana on 18 August 1750 in the midst of hurricane season bound for Spain. They passed Cape Canaveral on the Florida Peninsula on 25 August 1750 when the weather turned bad. The winds picked up and the ships were battered. The wind broke the tillers and ripped the sails of a couple of the ships and they began to take on water, so orders were given to throw the largest livestock, cannons, ovens, and damaged boats overboard. Over the next few days, the fleet lost most of its boats and had treasure and crewmen washing up on shores around the area. By 30 August 1750, the remnants of the fleet had reached the outer banks of North Carolina. Captain Bonilla made assessments and found that significant repairs would be needed before sailing again. Already, Englishmen were swooping in to scavenge cargo, money and sails off of the disabled Spanish ships. By 3 September 1750, the largest boat in the fleet had been maneuvered into some protection in the Ocracoke Inlet. Bonilla and some of his crew went shore for the night. A Bahamian boat quietly approached the ship, and were able to pirate a few things before being fought off by the crew that had remained on board.

The Governor of North Carolina, Gabriel Johnston, got his council together to try to figure out what to do with Bonilla and his disabled fleet. The customs people thought that Bonilla should be in trouble for illegally unloading cargo onto North Carolina soil. They wanted his cargo seized and duties collected. But the governor wanted to offer the fleet assistance and protection even though the Spanish hadn’t asked for any help. A member of the council was sent to talk to Bonilla to see what he needed. On his way, he learned that some locals from one of the islands which governed independently, not by North Carolina, had plans to raid the wreckage for anything they could find, using whatever force they needed to use. So, a request was made for a British warship to come and help, even if helping meant seizing the disabled boat.

A couple weeks later, on 19 September 1750, the Sloop Mary, owned and commanded by Captain Samuel Fitz Randolph left the Port of Perth Amboy, New Jersey bound for North Carolina. A man named William Waller was a sailor on the sloop. Waller, only weeks earlier, had married a woman named Margaret Fitz Randolph, a cousin of some sort of Captain Fitz Randolph. The Mary arrived in North Carolina about the same time as another sloop named Three Sisters¹, captained by Zebulon Wade.

On 5 February 1750/1, when the court heard the case of “the petition of Saml Fitz-Randolph in respect to some piratical practices on Board the Sloop Mary of Woodbridge, said Saml Fitz Randolph Master in North Carolina & Desired the Council to make Report thereon to him, what is proper to be done.” William Waller gave an account of their arrival. He said that they arrived a couple days after leaving New Jersey and saw a large Spanish ship at anchor in an inlet. The ship seemed to be in distress “having lost the Head of her fore mast and the head of her main mast, and her Mizzen mast quite gone and her Rudder.“

Waller said that the boatswain of the Spanish ship came on board the Sloop Mary and made an agreement with Samuel Fitz Randolph to carry a load of cargo for them to Norfolk, Virginia. William Waller said that he knew enough Spanish to act as an interpreter between Fitz Randolph and the Spanish boatswain. So, they made an agreement. Fitz Randolph would deliver the cargo to Norfolk in exchange for 570 pieces of eight. They had an agreement, but didn’t sign any papers. Spanish accounts of this incident say that Bonilla guardedly viewed the arrival of the two sloops as an opportunity. His ship was not very protected in its current location and any bad weather might hurt his ship further. So, Bonilla decided to hire the Mary and the other sloop.

About a week later, the Spanish boatswain named Rodriquez showed up with about fifteen crew members in a launch and “haw’d the said Sloop alongside the Spanish ship.” Then cargo was loaded from the disabled Spanish ship onto the Mary and the Three Sisters. While the transfer of goods was happening, the North Carolina governor’s representative arrived with a letter from the governor summoning Captain Bonilla to face charges of unloading cargo in the colony without permission. The Captain was surprised because he was expecting help, not a summons. The representative because suspicious of the intentions of the Mary and the Three Sisters though, and expressed his fears to the captain that the sloops would try to run away with the treasure. He offered to provide Bonilla with a sloop-of-war to use instead as long as the captain would accompany him to meet with the governor. Bonilla’s boatswain didn’t want the English government to get their hands on the cargo. He thought that if they did, he and the crew would never get paid.

Before leaving to meet the governor, Bonilla ordered a stop to the loading operations and to secure the remaining cargo. Some 55 chests of treasure and lots of goods were already loaded onto the Three Sisters. “Cocoa, cochineal, sugar and about 54 chests of money” had already been put on board the Sloop Mary. So, Bonilla left written instructions with Rodriquez to have the sails removed from the two sloops, carried ashore, and guarded until he returned. Without sails, the Three Sisters and the Mary couldn’t leave. He also ordered ten of his men put on each of the sloops to prevent any “underhanded actions.” The holds of both vessels in which the treasure chests had been stowed were ordered locked, barred and kept under constant guard.

So, as if this story didn’t have enough people in it already, there were a couple other guys who had been watching what was going on with the disabled ship, the sloops and the transfer of treasure. A man named Owen Lloyd approached a guy named William Blackstock, also known as William Davidson, with the idea of stealing away with the two sloops. It seems they hatched that plan with the agreement of the sloop captains Fitz Randolph and Wade. The captains were to remain below deck while Lloyd, his brother, Blackstock and their men make it look as though they had commandeered the two sloops to make off with the cargo. Once they escaped, they would sail to the West Indies and bury the treasure on an island known to Lloyd.

Rodriquez, the boatswain who had been left in charge, did not remove the sails from at least one of the sloops and did not post a guard on the Spanish vessel. So on 9 October 1750, the English pirates, led by Owen Lloyd, cut the cables of the sloops and put out to sea. The surprised Spaniards immediately pursued them in a longboat with guns firing. The Three Sisters got away and sailed for the West Indies. The Mary, however, had had damage earlier so wasn’t as fast. She ended up running aground and being captured by the longboat.

William Waller didn’t mention that they’d tried to run away with treasure when he told his tale at court. Instead, he said that a few days after the goods were transferred from the ship to the sloop, he and the Master of the Sloop (Samuel Fitz Randolph) had an argument, “some words happened,” and they agreed to part company. Waller left the Sloop Mary and boarded another sloop that was in the harbor bound for Middletown, New Jersey. But, he said that two or three nights before he left Sloop Mary, Joseph Jackson, a sailor on the Mary gave Waller about 450 pieces of eight tied up in a bag along with a letter directed to his father, James Jackson, in Woodbridge. Waller was to deliver 213 pieces of eight to James Jackson and to keep the remainder as his share. Waller said he was suspicious and believed the money to belong to the Spanish ship. Then Waller said he was informed by Thomas Edwards and Kinsey Fitz Randolph that they had cut a hole at the foot of the Lar-Board Cabin through the bulk head into the hold of the Sloop Mary where the money had been stored by the Spaniards. Waller said that the Spaniards had barred and locked the hatches and taken the keys with them in order to protect their goods. Waller stressed to the court that he had never taken any money out personally. But, he confessed that the money was divided among some of the crew of Sloop Mary. Kinsey Fitz Randolph, mate and son of the captain got a share. Samuel Fitz Randolph, Jr., another son of the captain got a share. Thomas Edwards, Benjamin Moore, Joseph Jackson and Silas Walker got shares. And lastly, Waller himself got a share.

The court asked Waller if Captain Samuel Fitz Randolph had known about the men taking the money, and Waller answered, “not to my knowledge,” but, when Waller and the rest of the crew went ashore for water, only the Captain and his two sons had remained on board. Waller claimed that Kinsey Fitz Randolph had told him that he had got 700 pieces of eight from the hold for his father, Captain Samuel Fitz Randolph and had taken 40 for himself.

The Captain of the other sloop, that Waller was now sailing upon, found out that Waller had Spanish money on board and said he wouldn’t have let him on board if he’d known. But Waller made it to Woodbridge on 16 October 1750. The next morning he gave Mary Jackson, Jr., the sister of Joseph Jackson, the letter he was to deliver as well as six pieces of eight. Then on Monday night (20 October 1750), he delivered 207 more pieces of eight to Mary, in the witness of Robert Fitz Randolph, Hartshorne Fitz Randolph, Mary Jackson, Sr., and Mercy Smith. Hartshorne Fitz Randolph was the one to take care of the money.

Waller explained that of his share, he had spent 68 pieces in New York, loaned 25 pieces to James Coddington, loaned 13 pieces to James Pike, loaned 5 pieces to Robert Fitz Randolph, loaned 3 pieces to Isaac Fitz Randolph, changed one piece for New Jersey money, and had the rest at the home of Robert Fitz Randolph in Woodbridge.

After Waller’s testimony, the Majesty’s council took the matter under consideration. They ruled that there seemed to be “great Reason to Suspect every one of the Mariners on Board the said Sloop to have been Guilty of Robbery and Piracy and some to suspect even the Petitioner, and Therefore that the prayer of the Petitioner had not been granted.” If we remember back to the beginning of this long tale, it was Captain Samuel Fitz Randolph who petitioned the court to find out what he should do about the pirated money and the claims of piratical practices. So, it seems that they were not believing that Samuel was innocent in this, or Waller either. Instead, the council recommended that each of the sailors should be apprehended and brought before the council individually, without the sailors being about to confer with one another, so the council could figure out what had really happened.

During the next six weeks, some of the crew were brought in and put in jail.

Waller managed to escape, but 317 pieces-of-eight were recovered and held in the treasury of New Jersey. Jonathan Belcher, governor of New Jersey was personally watching this case and having to report on it. There was a lot of political stuff going on between the British, the Colonies, and the Spanish. So, this really became an international incident. Lucky for Belcher, when he reported in to the British Duke of Belford on 1 July 1751, he could report that Waller had been recaptured and was being held for trial. A year later on 12 February 1752, there was an appeal from the pirates to be released from jail since they’d been jailed for six months with no charges filed. There isn’t any detail to say whether or not any of the Fitz Randolphs were jailed or punished. And lucky for us, our Robert just seems to have been a fairly innocent bystander in the story.²

Revolutionary War

As a Quaker, Robert Fitz Randolph was not active in fighting the Revolutionary War. Quakers did not bear arms or go to war. Many, even some of Robert’s relatives, including his namesake who was discussed earlier, broke with tradition and became Fighting Quakers. But it appears that Robert continued to observe the pacifist doctrine of his faith. He and his family would have been affected by the war, though, since it was happening all around them. In fact, General George Washington’s army passed through Woodbridge, New Jersey, where the Fitz Randolph family lived, on 28-29 November 1776 when they were retreating from Fort Lee across New Jersey, and Washington lodged in Woodbridge on 22 April 1789 when he had been elected president of this new nation and was making an inaugural tour to New York.

Robert Fitz Randolph was recorded on the tax list in 1779 at Woodbridge, Middlesex, New Jersey.

Death

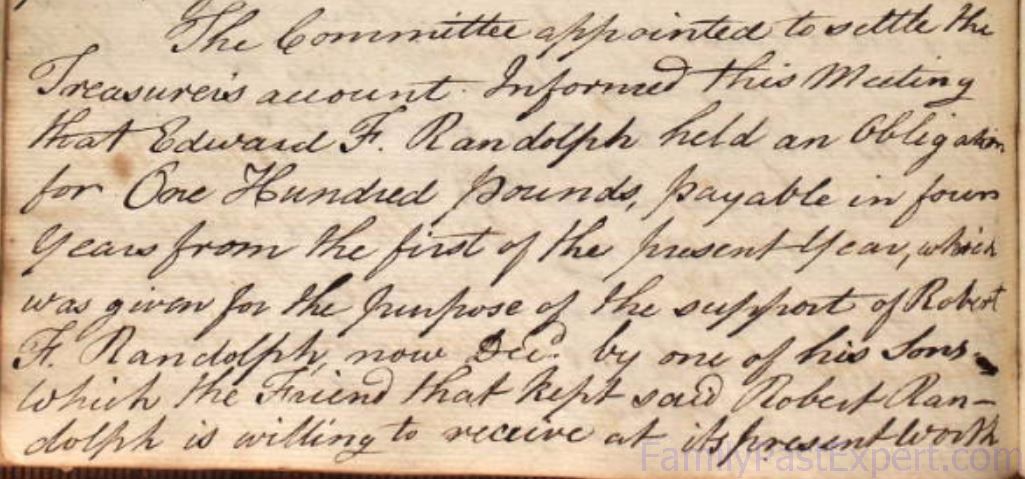

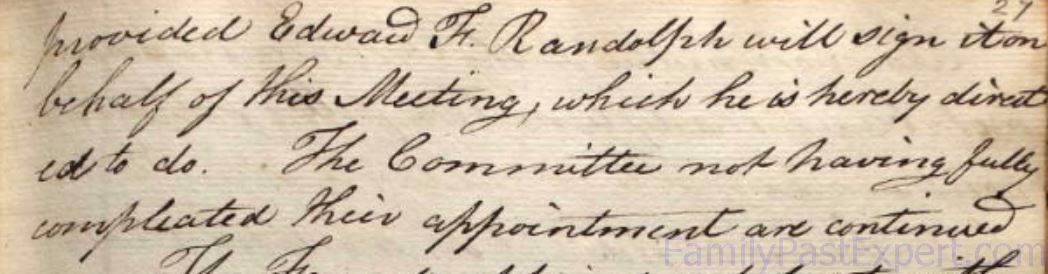

Robert Fitz Randolph died about 1803 in Green Brook, Somerset, New Jersey at about 90 years old. There was an item recorded in the Quaker minutes on 23 February 1803 regarding his death that indicates he was likely an invalid at the end of his life, which would be be expected for someone who lived such a long life.

Where is he in the tree?

Sources:

Ancestry.com, The New England Historical & Genealogical Register, 1847-2011 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011), ancestry.com, volume 097, page 334.

Ancestry.com, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014), Ancestry.com, Swarthmore College; Swarthmore, Pennsylvania; Births 1705-1901 Deaths -1705-1908 Marriages, 1712-1885; Collection: Quaker Meeting Records; Call Number: MR Ph:660. Record for Robert Fitz Randolph.

Ancestry.com, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014), ancestry.com, Haverford College; Haverford, Pennsylvania; Minutes, 1802-1834; Collection: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes; Call Number: U4.1.

Christian, Louise Aymar and Fitz Randolph, Howard Stelle, The descendants of Edward Fitz Randolph and Elizabeth Blossom 1630-1950 [ancestry] (East Orange, N.J.?: unknown, 1950), ancestry.com, p. 10.

Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, Volume XVI, Frederick W. Ricord (1891), pp. 277-284; Google books, Google Books (https://books.google.com/books?id=XC0UAAAAYAAJ).

“Documents relating to the colonial, Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary history of the State of New Jersey, Volume XIX,” (The Press Printing and Publishing Co., 1897: Paterson, N.J.) Archive.org, p. 66, Web, 18 July 2016, http://www.archive.org/stream/documentsrelatin19newjuoft#page/66/mode/2up.

Heit, Judi, “The Spanish Galleons ~ 18 August 1750,” North Carolina Shipwrecks, with Wilson, Doug, “Pieces of Eight,” 7 April 2012. Web, 18 July 2016, http://northcarolinashipwrecks.blogspot.com/2012/05/dangerous-shoals.html.

History of Crawford County, Pennsylvania: Containing a History of the County., (1885), pp. 179-181, Google Books (https://books.google.com/books?id=_MkwAQAAMAAJ).

Vail, William Penn, Genealogy of some of the Vail family descended from Thomas Vail at Salem, Mass., 1540 together with collateral lines [database on-line] (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1937), ancestry.com, p. 76.

“Revolutionary War Sites in Woodbridge, New Jersey,” Revolutionary War New Jersey: The online field guide to New Jersey’s Revolutionary War Historic Sites,” Web, 17 July 2016, http://www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/woodbridge_nj_revolutionary_war_sites.htm.

Notes:

¹ In some accounts, the second sloop was called The Seaflower rather than Three Sisters.

² For a much more detailed version of this incident, see The Spanish Galleons ~ 18 August 1750.

Leave a Reply